In the effort to increase quality assurance and to avoid counterfeit of alcohol, researchers have come up with a new technique, where they analyze residues from evaporated bourbons. And of course, where else would a study like this be conducted other than the University of Louisville, in Kentucky-the state where there are twice as many barrels of aging whiskey as there are residents.

In a recent report published in Physical Review Fluids, researchers report that different types of American whiskey form unique web-like patterns after evaporation. This technique, as the researchers report, could not only identify counterfeit alcohol but also lead to new techniques to speed up whiskey aging.

Concentration is essential

In their experiment, the researchers evaporated bourbon droplets, which were previously diluted in the water of different amounts. After evaporation, they examined the residues under a microscope. They found out that alcohol samples having concentrations of at least 35% left films that were similar to those formed in Scotch whisky. At lower concentrations of 10%, the patterns left after evaporation were similar to coffee rings.

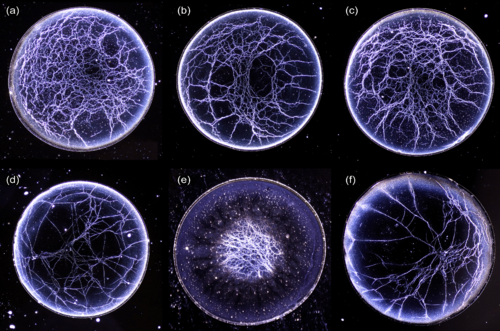

Then, somewhere between these two concentrations gave the answer to seeing the unique fingerprints of various American whiskeys. When diluted to around 20%, almost every American whiskey sample left behind unique microstructures that resembled spider webs.

In the following image, the leftmost shows what is left by whiskey at 35% alcohol concentration; the one in the center shows the web-like structures formed by whiskeys diluted to 20%; and the rightmost image shows markings left by whiskey at a lower concentration at 10% The difference in the 'fingerprints' show that concentrations affect the way the compounds mix and interact on a molecular level to be able to form webs.

Web Microstructure Implications

Fluid dynamics researcher at the University of Louisville, Stuart Williams explains how the hydrophobic nature of these compounds cause this pattern to form. "A lot of [those compounds] do not like water," he says, "so diluting the bourbon forces those particles to flee toward the surface and form a skin over the droplet. As the liquid evaporates away, film contracts and buckles to create a network of wrinkles."

Williams continued to explain that each brand has its own composition, so naturally, each brand will leave a different web pattern. He also goes on to talk about how samples of higher concentrations would not form the same pattern since there is relatively a small amount of water and the compounds will not move toward the surface of the droplet. On the other hand, at lower concentrations, there are not enough compounds to move around.

The researchers were not able to obtain the same results with Canadian or Scotch whiskies, which led them to the hypothesis that the formation of web-like microstructures could be attributed to the American distillation process. Compounds from charred oak barrels leach into the whiskey while aging. And because Americans use new barrels as opposed to reusing them, the technique allows for more compounds to move around. This then led to the next step of their research, where they plan to include tracer molecules in the samples to be able to take microscopic videos of the evaporation process.