An impending environmental disaster is looming in Guadalajara in western Mexico as the Santiago river releases a stench brought on by years and years of industrial waste and sewage. The residents are understandably alarmed at the smell emanating from the river's water that hovers over crops and fouling the tap water at home.

A SLOW-MOTION CHERNOBYL

Residents and environmental activists point at chemicals from factories largely contributing to the toxicity that already got nearby residents sick, if not killed. Although Mexico recently entered a trade deal with the United States and Canada and made a promise of being mindful of the environment, institutions and residents would argue that Mexico cannot keep its end of the bargain in that trade deal unless some serious overhaul in its legal framework and a dire change in its political conditions are done.

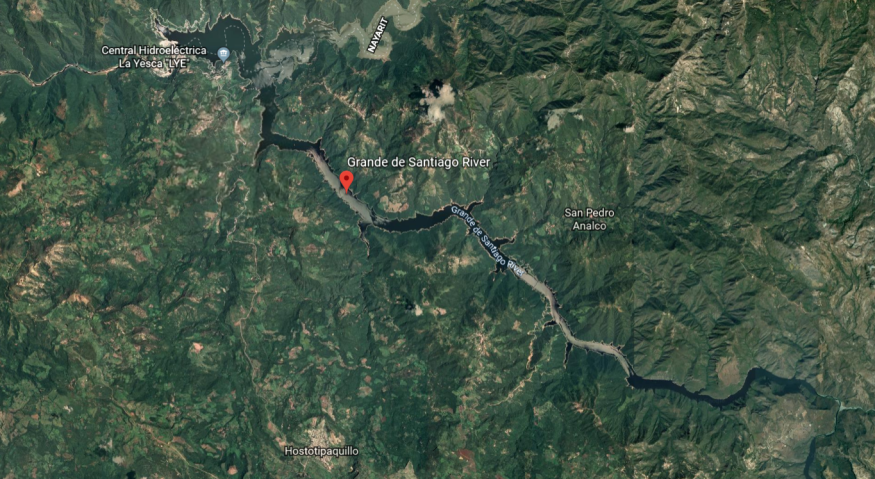

Santiago river is a testament to the failure of the government to put companies and factories that violate environmental laws under necessary sanctions. The situation in the river is dire that even the United Nations called it the country's most polluted waterway. For a long time, farms and factories were the primary contributors to the illegal quantities of waste dumped into the Santiago river and faced a little penalty. These factories are required by law to report and treat their emissions, and this is all done in good faith which even officials admit does not work.

A DIRE WATER CRISIS

Mexico's National Water Commission (Conagua) announced in a recent conference that only a third of the country's industrial wastewater is treated based on studies done in 2017. Although there are companies that comply and treat their wastewater Conagua director Bianca Jimenez says there are companies that don't although they have every means to do so. "And there the state has to intervene," she says. However, the state rarely does.

The commission is the one responsible for the regulation of industrial emissions into rivers however, for the whole state of Jalisco there is only one inspector. Add to that, during the rare time the state responds to the penalties committed by the factories, the consequences are quite minimal. For instance, according to the New York Times, Texas-based Celanese Corp acknowledged that it had discharged illegal amounts of chemical waste during the summer of 2015 for 13 times including 500 kilograms of corrosive compound hydrochloric acid. The company's defense said the heavy rains caused the overflow. Conagua penalized the company with a $4, 300 fine.

Mexico's environmental enforcement agency is also an authorized institution to inspect industrial wastewater but it rarely does its job as well. The agency's inspectors, for instance, visited 73 companies out of 10,000 companies (including family-owned and state-owned companies) around the Santiago river basin within five years leading up to 2018 to check water emissions.

A DANGEROUS CYCLE

The issue of the Santiago river's dire situation is not new -- and it isn't something Mexican officials haven't heard of before. An accident brought the world's attention to the dire situation of the Santiago river's pollution back in 2008 when an 8-year-old boy named Miguel Angel Lopez Rocha fell to a tributary of the river and although he got out, he began vomiting later on and died days later. The reason? Arsenic poisoning from the river, according to the National Human Rights Commission.

A 2011 report supported the claims of the high toxicity of the river. The Mexican Institute for Water Technology was commissioned by the government to conduct a study on the river and the researchers found high levels of arsenic, lead, cadmium, cyanide, mercury, and nickel in the water. Various studies were later done and the results are still the same, showing dangerous levels of toxins.