Last 2019, scientists from the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON) strapped three dead alligators to harnesses and deposited them 6,600 feet down in the Gulf of Mexico as a part of the experiment to understand how the invertebrates survived in the ancient oceans and how the carbon from the land makes it to the deep-ocean.

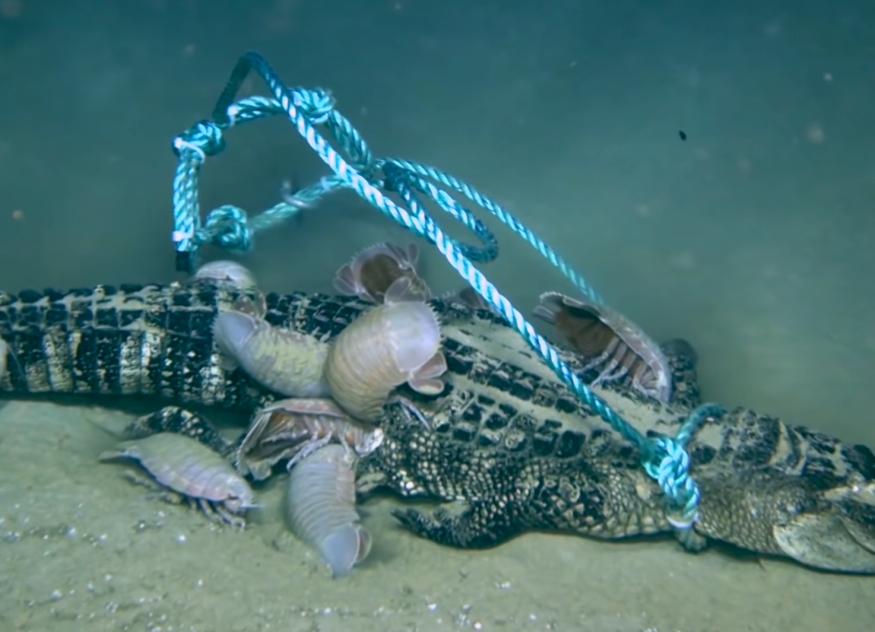

Upon the release of the alligator corpses, the first gator was feasted upon by giant isopods after less than 24 hours. The second alligator was devoured down to its skull and spine in a span of 51 days. No one knows what happened to the third alligator yet as the predator left nothing but the torn rope. The study, which was published in PLOS One, also aims to test how the creatures living in the deep-sea would react to a food source that they have never seen before -- in this case, the carcasses of three freshwater alligators.

Dr. Clifton Nunnally, the co-author of the paper, explains that the deep-ocean is not necessarily a friendly place. He describes the deep-ocean as something like a food desert with limited spots that serve as food oases. "Some of these oses are vents on the ocean floor. Sometimes this is where chemicals come out and sometimes this is where food from the surface ends up," he said.

According to the scientists behind the study, food falls are not entirely new, however, most of the food falls done in the past have focused on large mammals especially whales. The corpses of whales usually serve as a banquet for various creatures in the ocean may they be fishes or invertebrates. Meanwhile, corpses of freshwater alligators are known to be cast into the ocean especially when there are hurricanes and extreme weather although the effects and aftermath of the gator fall have not yet fully observed until recently.

In a video published by LUMCON back in April, it is seen that in less than 24 hours that the researchers left the corpses, the first gator was shown to be swamped by huge isopods specifically the Bathynomus giganteus and some of these creatures were able to get through the thick hides of the alligator and ate it from the inside. This amount of food will be stored inside the isopods' body, giving them enough energy for months or even years. The second freshwater alligator was picked clean when the researchers revisited the site 51 days later. However, they noticed that the bones were caked in a mysterious brown substance.

The researchers quickly analyzed the mysterious brown substance and found out through DNA analysis that it is a newly discovered bone-eating worm which is classified under the genus Osedax. In addition, the researchers noted that this is the first time that a species of Osedax is present in the Gulf of Mexico. The most mysterious, however, is what happened to the carcass of the third freshwater alligator. Unfortunately, it disappeared from its harness before the researchers were able to see if it was eaten by a marine creature. They assumed that it was taken by a larger predator -- one capable of hauling the combined weight of the carcass and the harness -- and they assumed it the likeliest culprit is a shark.

© 2025 ScienceTimes.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission. The window to the world of Science Times.