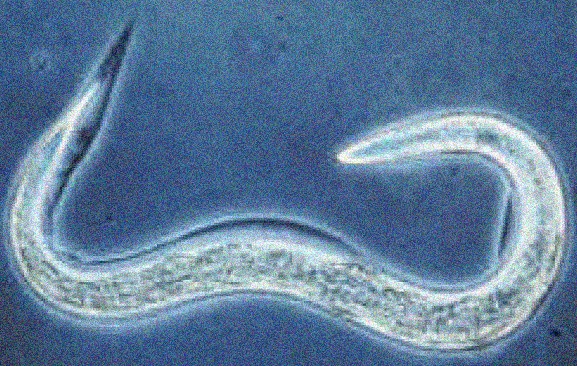

Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is a type of roundworm that is programmed to die to lower the colony's demand for food, according to Daily Mail.

Dr. Evgeniy Galimov, the first author of the study from the University College London (UCL) Institute of Healthy Aging said, "there is programmed organismal death as well, that can benefit animal colonies."

He added, "they show how increasing food availability for your relatives by dying early can be a winning strategy, which we call consumer sacrifice." They have a life-shortening mechanism that turns on when the worm reaches a certain age.

For the future of the colony

Once they die, they will also benefit young worms in the colony because there is more food to go around. But mutations can turn off their self-destruct program, extending their lifespan.

Read now: Human Cyborg! Girl Aged 14 Gets a 3D-Printed Hero Arm and is Now Learnign How to Ride a Bike

The researchers hypothesized that "colonies of closely-related individuals - such as C. elegans - evolved to develop a programmed death mechanism," said Daily Mail. To test this, the researchers created a computer model of a colony of C. elegans with limited food. They also took a look at the impact of their pre-determined death on their reproductive span.

Once the simulations ended, they discovered that a shorter lifespan and reproductive span, as well as a reduced adult feeding rate, increases a colony's fitness. They said the early death of an adult is beneficial, especially when the colony's food consumption rate is relatively high.

However, Professor David Gems from UCL's Institute of Healthy Aging said those that die for others cannot evolve.

"According to evolution theory, altruistic death to leave more food to your relatives normally can't evolve," he said. The tendency of other colony members is to consume the resources left by those who have died, which Gems calls "a tragedy of the commons."

But the tragedy doesn't happen in C. elegans colonies.

An important scientific discovery

A non-parasitic species of the nematoda phylum, they live in colonies of identical worms, preventing other worms from invading and getting all their food.

Aside from being programmed to die, C. elegans share genes with humans who lived in the pre-Cambrian era, which was 500 to 600 million years ago, according to The Lundquist Lab.

The article refers to the urbilaterian ancestor, the relative of all multicellular organisms on earth. It includes invertebrates, such as insects, nematodes, sea urchins, as well as vertebrates, like mammals, fish, reptiles, and birds.

Read now : Astrophysicists Perform String Theory Test To Find Out More About A Still-Undetected Particle

The urbilaterian ancestor had nearly all of the genes and genetic mechanisms governing modern organismal development, the article added. Other animals also share these traits, such as humans and nematodes.

Sharing the same ancestor gave C. elegans nematodes things that humans have, such as neurons, skin, gut, muscles, and tissues. They were identical in terms of form, function, and genetics.

Humans don't have the adaptive death that C. elegans, but some salmon do. They spawn and die as they swim the upper reaches of rivers. Like the C. elegans, they salmon die so they could "nourish the salmon fry," in a process called adaptive biomass sacrifice, said the researchers.

© 2025 ScienceTimes.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission. The window to the world of Science Times.