Scientists at the University of Cambridge have recently found a key indication that the fetus is using to regulate its nutrient supply from the placenta, showing a tug-of-war between genes they have inherited from their father and their mother.

According to EurekAlert! The research performed in rodent models could help explain why some babies are growing poorly in the womb.

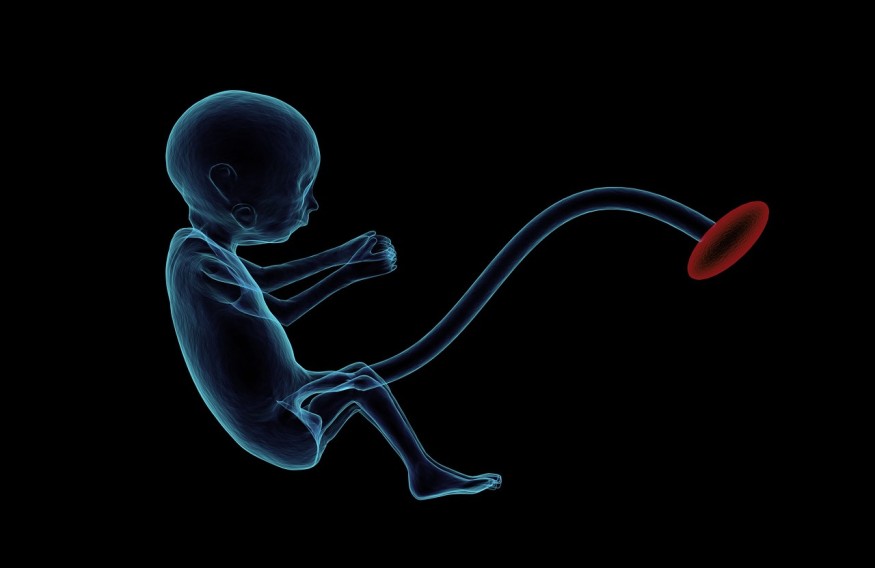

As the size of the fetus grows, there is a need for it to communicate its growing demands for food to the mother. It receives its nourishment through blood vessels in the placenta, a specialized organ containing cells from both the mother and her baby.

From 10 to 15 percent of babies grow poorly in the womb, frequently showing reduced growth of blood vessels in the placenta.

Meanwhile, the blood vessels are dramatically expanding between mid- and late-gestation in humans, approaching a total length of roughly 329 kilometers at term.

Encouraging Blood Vessel Growth within the Placenta

A research team led by the University of Cambridge scientists used genetically engineered mice to present how the fetus produces an indicator to encourage blood vessel growth within the placenta.

This signal is also causing modifications to other cells of the placenta to enable more nutrients from the mother to go through the fetus.

According to the first author of the paper, Dr. Ionel Sandovici, as the fetus grows in the womb, it needs food from its mother. Healthy blood vessels are essential in helping it acquire the correct amount of required nutrients.

Dr. Sandovici explained that they have identified one way the fetus communicates with the placenta to prompt the right expansion of the blood vessels. When the said communication breaks down, the blood vessels do not develop properly, and the "baby will struggle to get all the food it needs," he added.

The IGF2 Signal

The research team discovered that the fetus is ending a signal identified as the IGF2 that reaches the placenta through the umbilical cord.

In humans, the IGF2 levels in the umbilical cord gradually increase from 29 weeks of gestation through the term in which too much IGF2 is linked to too much growth, while insufficient IGF2 is linked to extremely little growth, a similar New York Post report specified.

Essentially, babies that are not quite large or extremely small are more potential to suffer or even die at birth. They also have a higher risk of developing other conditions like diabetes or heart ailments as adults.

Describing the said signal, Dr. Scandovici explained, it's been known for some time that IGF2 is promoting the organs' growth where it is generated.

The team showed that IGF2 is also acting as a classical hormone. It is produced by the fetus, goes into the fetal blood through the umbilical cord and to the placenta.

Study in Mice

In mice, a reaction to IGF2 in the placenta's blood vessels is mediated by another protein identified as IGF2R. The two genes producing IGF2 and IGF2R are imprinted, a process by which molecular switches on the gene identify their parental origin and can turn such genes on or off, Medical Xpress reported.

In this circumstance, only the copy of the IGF2 gene inherited from the father becomes active, while only the IGF2R copy inherited from the mother becomes active.

According to the study's lead author, Dr. Miguel Constancia, one theory on imprinted genes is that genes that are paternally expressed are "greedy and selfish."

The researchers wanted to extract the most resources possible from the mother because maternally-expressed genes act as countermeasures to balance such demands.

The results of the study were published in Development Cell.

Related information about genomic imprinting is shown on Javier Novo's YouTube video below:

RELATED ARTICLE : Study Offers Hints on the Reason Pregnancy May Raise Danger of Rejection of Organ Transplant

Check out more news and information on Medicine & Health in Science Times.

© 2025 ScienceTimes.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission. The window to the world of Science Times.