Compared to men, the general public has a limited understanding of how women experience disease. Biomedical research is crucial in helping researchers better understand the timeline of diseases and how they can be treated. However, in the past, most research has been conducted on male cells and experimental animals, such as mice, with the assumption that the results can be applied to females as well.

This is a flawed approach, as men and women experience the disease differently. This includes differences in the development of diseases, the length and severity of symptoms, and the effectiveness of treatment options. Therefore, scientists must conduct more research on women and consider these differences to improve one's understanding and treatment of diseases in both men and women.

Despite the growing recognition of these differences, the underlying reasons for them are not fully understood. As a result, women often face worse outcomes when it comes to health and treatment.

Adverse Drug Reactions to Women

For example, women experience 50-75% more adverse reactions to prescription drugs than men. This has led to many drugs being withdrawn from the market due to concerns over their potential health risks for women. One proposed explanation for this disparity is that sex differences in body weight may play a role in the way that drugs affect women. However, further research is needed to fully understand the causes of these differences and how they can be addressed.

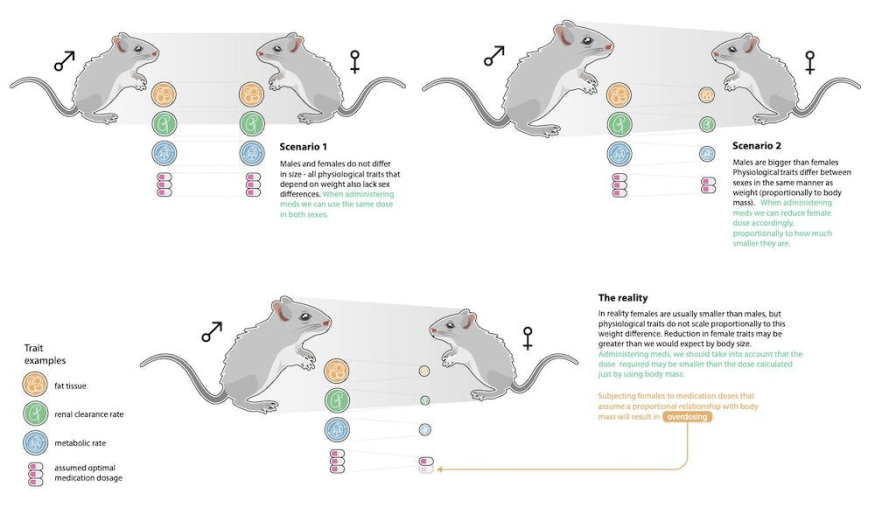

It has been suggested that adjusting drug doses based on body weight may help to alleviate adverse reactions in women by providing them with lower doses. However, recent research published in Nature Communications challenges this assumption. The study found that the "smaller version" theory, which posits that females are simply smaller versions of males, does not hold for most preclinical traits, such as glucose levels. This suggests that adjusting doses based on body weight alone may not be effective in reducing drug reactions in women.

The reliance on research conducted on men to inform health care decisions for women, and vice versa, can have significant consequences. In the case of adverse drug reactions, these impacts are both clinical and economic. For instance, a recent study estimated that 250,000 hospital admissions in Australia each year are due to medication-related issues, costing the healthcare system around $1.4 billion annually. Adverse drug reactions have also been shown to prolong hospital stays, with patients admitted for such reactions staying for a median of eight days in a large UK study.

Women are often the ones who discontinue their medications due to adverse reactions. If weight-adjusted dosing of drugs could reduce these reactions, women would likely see greater benefits from the health care system.

ALSO READ : Psychological Trauma May Impact Women During Pregnancy, Childbirth and Afterbirth, Study Says

Proof of Studies

While there is some evidence that weight-adjusted dosing can be effective for certain drugs, it is not clear whether this approach will work for all drugs. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already recommended dosage changes for women for some drugs, such as the sleep aid zolpidem. Weight-adjusted dosing has also been shown to be effective for certain antifungal drugs and antihypertensive drugs.

However, drug reactions in women are often linked to how the drug works in the body, rather than body weight. There are also documented physiological differences between men and women that can affect how drugs are absorbed and cleared by the body, independent of body weight.

To better understand these complex relationships, a more comprehensive approach is needed. In the study, the scientists used a method commonly used in evolutionary biology, known as "allometry", to examine the relationship between preclinical traits and body size on a log scale. This allowed them to better understand the underlying factors that influence drug reactions in women.

The study researchers applied allometry analyses to 363 pre-clinical traits in males and females, comprising over two million data points from the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium. They focused on mice, one of the most commonly used disease model animals, and examined whether sex differences in pre-clinical traits, such as fat mass, glucose levels, and LDL cholesterol, could be explained by body weight alone.

Sex-Based Medication

The analyses revealed sex differences in many traits that could not be explained by body weight differences alone. These included physiological traits such as iron levels and body temperature, as well as morphological traits like lean mass and fat mass, and heart-related traits like heart rate variability.

Furthermore, the team found that the relationship between a trait and body weight varied widely across all the traits they examined, indicating that the differences between males and females cannot be generalized. This means that females are not simply smaller versions of males.

Ignoring these differences in some cases, such as measures of blood cells, bone, and organs could result in missing a significant portion of the population variation for a particular trait: up to 32% for females and 46% for males. Such findings suggest that people need to consider sex differences in drug dosing on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the specific traits and factors that may influence drug reactions in women.

In an era where personalized medicine and patient-specific solutions are becoming increasingly feasible, it is clear that sex-based data are crucial for advancing health care equitably and effectively. The study sheds light on how males and females can differ across many preclinical traits, highlighting the need for biomedical research to focus more closely on measuring and understanding these differences.

When a relationship between sex and drug dose is identified, the data suggest that the dose response is likely to be different for males and females. This means that a one-size-fits-all approach to drug dosing is unlikely to be effective. The methods used in their study can help to clarify the nature of these differences and provide a way forward for reducing drug reactions in women.

RELATED ARTICLE: Loss of Male Sex Chromosome Linked to Negative Health Impacts and Early Death Than Women

Check out more news and information on Medicine & Health in Science Times.

© 2025 ScienceTimes.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission. The window to the world of Science Times.