Scientists studying the Earth have used the minute differences in hydrogen atoms to understand our planet's ancient history. A recent study suggests that these identical particles could also lead to new ways of detecting the growth of cancer cells.

Understanding Cancer Metabolism

Under normal conditions, the cells of organisms such as animals and yeast generate energy through respiration. In this process, they consume oxygen and release carbon dioxide as a by-product. In the case of cancer, the cells' metabolism differs from the cells growing next to them.

In nature, hydrogen has two main isotopes: deuterium and ordinary hydrogen. Deuterium is slightly heavier, while hydrogen is slightly lighter. Here on Earth, hydrogen atoms outnumber deuterium atoms in a 6,420:1 ratio.

Surprisingly, hydrogen atoms are known to reach cancer cells. These atoms may come from an enzyme called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Among its many roles, NADPH gathers hydrogen atoms and passes them to other molecules while making fatty acids.

However, NADPH does not always come from the same source of hydrogen. Previous studies suggest that NADPH may use different hydrogen isotopes more or less often depending on what the other enzymes in a cell are doing. This raises the question of whether cancer can rewire the way NADPH gets its hydrogen and ultimately alter the atomic composition of a cell.

Atomic Cancer Fingerprints

Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder and Princeton University discovered that cancer cells may have a different assortment of hydrogen atoms than healthy tissue. These findings can provide health experts with new approaches to studying cancer growth and spread and lead to novel ways of detecting cancer early in the body.

Led by CU Boulder geochemist Ashley Maloney, the research team examined cancer at the atomic level, adding a whole new dimension to medicine. The details of the study were discussed in the paper "Large enrichments in fatty acid 2H/1H ratios distinguish respiration from aerobic fermentation in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae."

For many years, experts from various fields have turned to the natural distribution of these atoms to reveal evidence about the history of Earth. For instance, climate scientists examine samples of hydrogen atoms trapped in the ice in Antarctica to find out how hot or cool our planet was hundreds of thousands of years ago. In the new study, the research team wondered if these same atoms can offer hints about the lives of complex biological organisms.

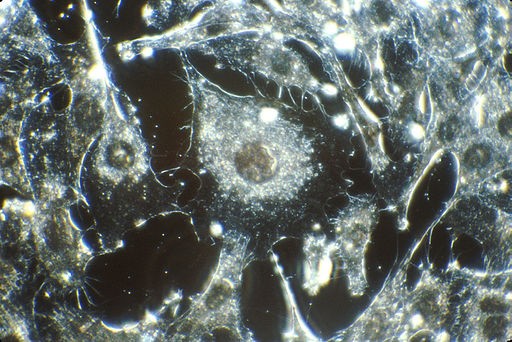

To find out, researchers set up jars full of flourishing yeast colonies in laboratories at Princeton and CU Boulder. In a separate setup, scientists at Princeton performed an experiment with colonies of healthy and cancerous mouse liver cells. Then, the research team obtained the fatty acids from the cells and identified the ratio of hydrogen atoms within using a mass spectrometer.

They discovered that cells that grow fast, like cancer cells, have a much different ratio of hydrogen versus deuterium atoms. Fermenting yeast cells were found to possess about 50% fewer deuterium atoms on average than normal yeast cells. Since fermenting yeast cells resemble cancer cells, cancerous cells exhibited a similar but not as strong shortage in deuterium. It is as if cancer cells left a fingerprint on a crime scene.

RELATED ARTICLE : Self-Assembling Molecules Has Promising Help in Cancer Therapy

Check out more news and information on Cancer in Science Times.