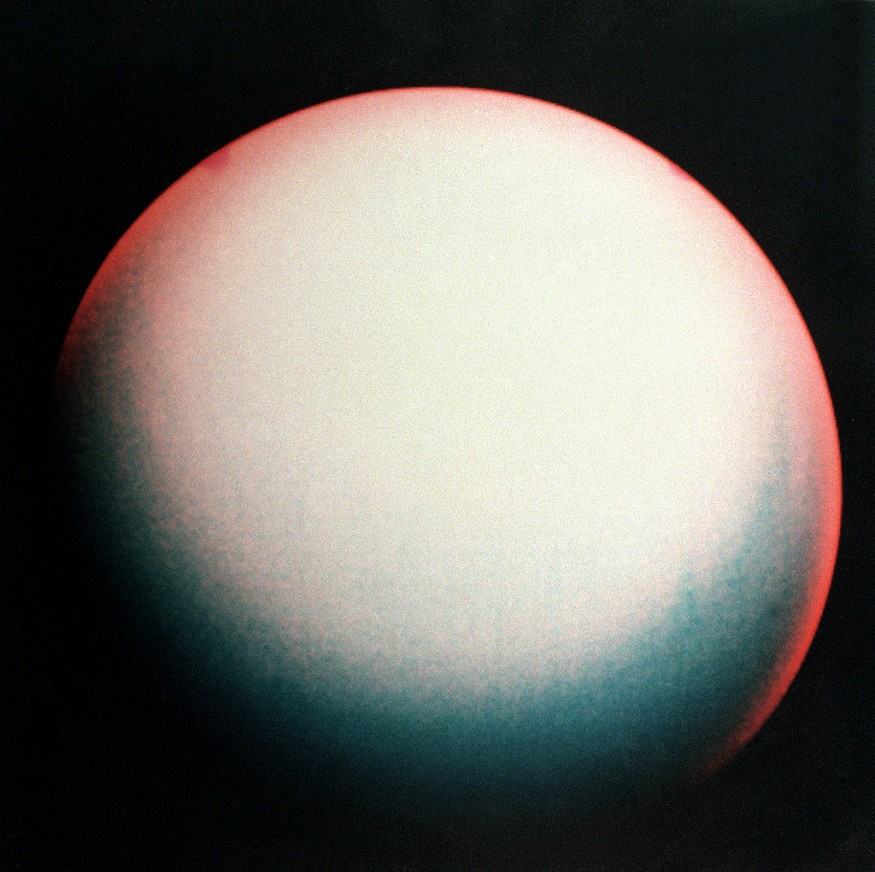

Uranus, the pale blue-green giant lurking 1.6 billion miles from Earth, has always intrigued astronomers with its unusual tilt and icy atmosphere.

Now, a series of groundbreaking studies has shed new light on this distant world and its moons, unveiling mysteries that challenge what we thought we knew.

A major finding centers on Miranda, one of Uranus's moons, which scientists now believe has an ocean beneath its icy surface.

NASA's Voyager 2 Data Uncovers Potential Habitable Zone Beneath Miranda's Ice

This discovery, based on data from NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft, hints at the possibility of a habitable environment deep within Miranda's frozen crust.

Such subsurface oceans are key areas of interest for astrobiologists, as liquid water is a fundamental ingredient for life.

According to Salon, Miranda's icy shell is thought to be about 18 miles thick, covering an ocean that could extend more than 60 miles below.

Researchers suspect that tidal forces from Uranus help keep this hidden ocean liquid. While it's too early to say if this means life exists there, it raises exciting possibilities about the potential for more discoveries in Uranus's moons.

But the surprises don't stop there. Voyager 2 also revealed puzzling details about Uranus's magnetosphere, the protective magnetic field that shields the planet from harmful solar particles.

Unlike Earth's magnetic field, which is orderly and anchored by its iron core, Uranus's magnetosphere is chaotic and lopsided. For decades, scientists couldn't explain why.

Voyager 2 Flyby: Solar Winds Distorted Uranus's Magnetosphere Data

Recent analysis has provided answers. The magnetosphere's strange behavior is likely due to a solar wind event — a burst of charged particles from the Sun — that compressed Uranus's magnetic field right before Voyager 2's flyby, Brightside said.

This unique timing distorted the data and left scientists scratching their heads for decades. Now, they realize it was a case of bad timing: a week earlier or later, and the observations would have painted a very different picture.

Uranus also seems to have a peculiar internal structure. A study using advanced computer models suggests that the planet has distinct layers within its core, like oil and water that never mix.

This layering disrupts large-scale convection, which could explain Uranus's unusual magnetic field. Similar findings apply to Neptune, its icy neighbor, showing that these two planets have more in common than previously thought.

Despite these breakthroughs, Uranus remains one of the least studied planets in the solar system. Only Voyager 2 has visited, and no follow-up missions are planned until the 2040s.

For now, scientists must rely on existing data and computational models to uncover more about this enigmatic planet and its moons. One thing is certain: Uranus holds more surprises than we ever imagined.

© 2025 ScienceTimes.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission. The window to the world of Science Times.