NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has once again revolutionized our understanding of the cosmos.

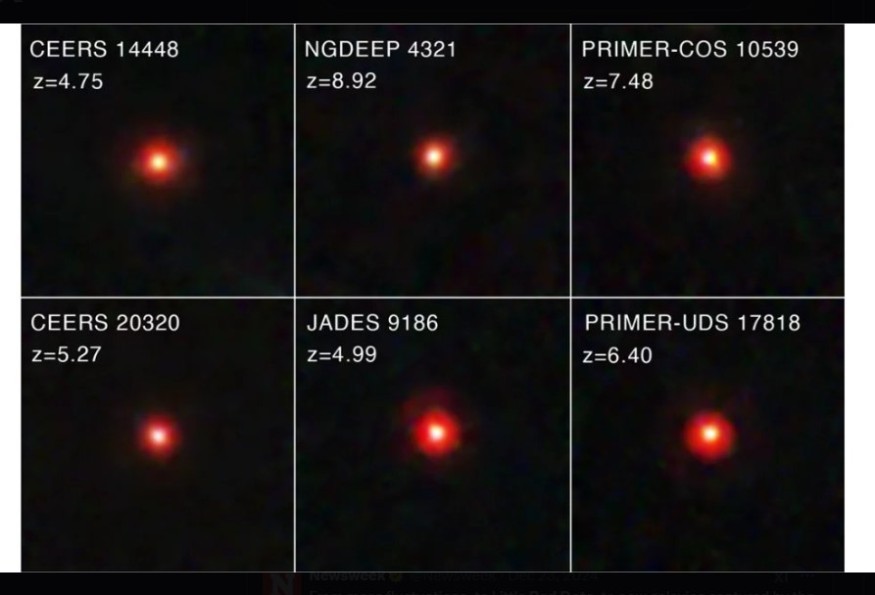

Among its latest breakthroughs is solving the puzzle of the mysterious "little red dots" (LRDs) discovered in images of the early universe.

James Webb Telescope Identifies Mysterious Red Dots as Active Black Hole Galaxies

These tiny, red objects baffled scientists because they appeared in a time when galaxies were thought to be far less developed. Now, astronomers have identified these dots as something even more fascinating: growing supermassive black holes.

The LRDs were first spotted in 2023, less than a year after the JWST began its mission.

According to Salon, these dots appeared in photographs of galaxies formed less than a billion years after the Big Bang, a period when such massive formations were considered unlikely.

The existence of these objects challenged long-standing cosmological theories, earning them the nickname "universe-breaking." However, recent research led by Dr. Dale Kocevski of Colby College reveals that these enigmatic dots are active galactic nuclei (AGN), galaxies with central black holes emitting intense light as they consume surrounding matter.

Dr. Kocevski and his team analyzed data from the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey and other extragalactic studies.

Their findings showed that about 81% of the LRDs had characteristics consistent with AGN.

By identifying the light signatures from both stars and black holes, the team was able to estimate the mass of these galaxies and their central black holes.

Cosmic Dust and Black Holes: How New Findings Challenge Galaxy Growth Models

This discovery resolves a key mystery. Initially, scientists thought the LRDs were enormous galaxies, which implied that they had formed too quickly to align with current models of galaxy formation.

Kocevski's research shows that much of the light attributed to stars is actually coming from the black holes, SciTechDaily reported.

This adjustment places the galaxies within expected growth patterns, solving the "too massive, too early" problem.

Yet the findings raise new questions. Steven Finkelstein, a co-author from the University of Texas at Austin, noted that LRDs seem to vanish about 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

The dusty environments make the light from these objects appear red, but as the galaxies evolve, they shed this dust, becoming less obscured and more visible at other wavelengths.

Interestingly, LRDs do not emit strong X-rays, which is unusual for black holes. This may be due to dense gas surrounding the black holes, trapping X-ray photons. Scientists are now studying the mid-infrared properties of LRDs and conducting deeper spectroscopic observations to unravel more details.

Dr. Kocevski highlighted, "We are witnessing the early growth of supermassive black holes that anchor today's massive galaxies."