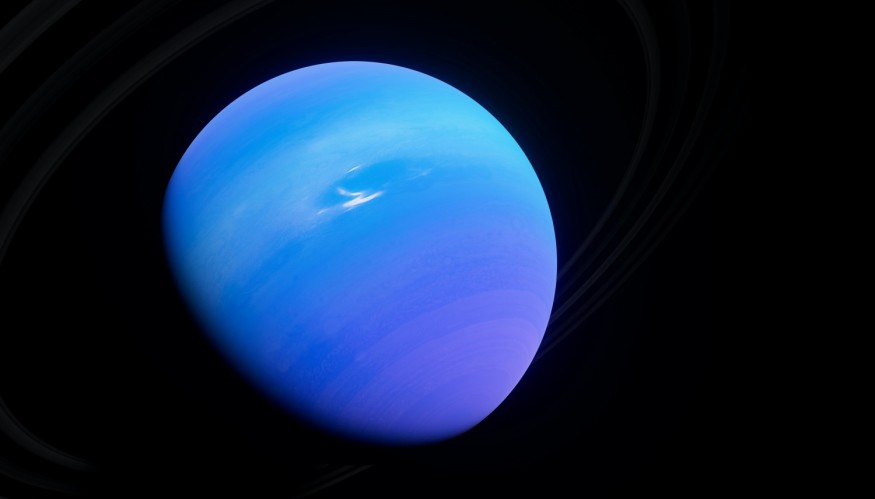

The turquoise oddball of the Solar System, Uranus, may have joined other planets in hosting at least one icy moon that is pumping materials to the planetary system.

A new study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, re-analyzed the 40 years' worth of data from NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft, the only spacecraft to have gone to Uranus. As per Futurism, the team detected energetic plasma particles being expelled into surrounding space by one or both of Uranus' moons, Ariel and/or Miranda.

Mystery of Plasma Particles Released into Space

Their study, titled "A Localized and Surprising Source of Energetic Ions in the Uranian Magnetosphere 1 Between Miranda and Ariel" recently accepted for publication in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, suggests that one or two of Uranus' 27 moons might have oceans beneath their icy surfaces and are actively spewing material, possibly through plumes.

Voyager 2 obtained the sole in-situ observations of Uranus and its system during its three-day visit to the planet in 1986. A recent examination of these decades-old measurements has uncovered an enigmatic source of energetic ions in the planet's magnetosphere.

The spewed particles from Miranda and Ariel looked to be clumped around Uranus' magnetic equator, which piqued the scientists' interest. That is strange because magnetic forces should lead the particles to scatter and spread throughout the globe.

Unless, there was a continual supply of magnetized particles from a neighboring moon which is released as a vapor plume from an ocean somewhere under its frozen surface.

Lead author of the study Ian Cohen, a space scientist at APL, explained that they initially thought these characteristics were due to Voyager 2 passing through a random stream of plasma injected from the far tail of Uranus' magnetosphere. But that was not true since an injection would normally have a far wider distribution of particles than what was observed.

Oceans in Two Moons of Uranus

Their findings started a mystery that researchers attempted to reproduce the observations from Voyager 2 spacecraft using physical models and used the data for subsequent knowledge, Tech Explorist reports.

They came to the conclusion that the true explanation requires both a powerful, consistent supply of particles and a specific mechanism to activate them. After considering several possibilities, they decided that the particles were most likely emitted from a neighboring moon.

The team suspects that Ariel or Miranda is responsible for the particles, either through a vapor plume similar to that of Enceladus or by sputtering, a process in which high-energy particles collide with a surface and propel additional particles into space.

According to modeling, the energizing process would therefore be the same: the moons continually expel particles into space, where they form electromagnetic waves. These waves accelerate some of the particles to the energy that the LECP can detect. The team hypothesizes that this approach kept the particles observed by LECP so tightly confined.

Cohen said that, with only a single observation of the region and a lack of data about the plasma composition or the measurements of the full range of electromagnetic waves in it, there is no way to definitively identify the source of the plasma.

Despite this, scientists have theorized that Ariel and Miranda may contain subsurface oceans. Both moons' photos from Voyager 2 show visible traces of geologic resurfacing, including probable eruptions of frozen water on the surface.

RELATED ARTICLE: Two Newly Discovered Forms of Salt Water Ice May Exist on Faraway Moons; What Could This Imply?

Check out more news and information on Space on Science Times.