Dopamine is known to control the brain's reward system, resulting in happy, feel-good emotions. More than telling the brain what to feel, a recent study describes how dopamine may be dictating economic decisions as well.

The neurotransmitter, or chemical messenger, is made in two small areas of the brain called the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area. Normally associated with pleasure, the flipside of dopamine has been linked to addiction, as well.

A previous study analyzing the downer side of the hormone looks at how drug addicts will take risks just for the reward of another dose. On the other hand, the lack of dopamine is responsible for illnesses such as depression, schizophrenia, and Parkinson's disease.

"Having separate neuronal correlates for appetitive and aversive behavior in our brain may explain why we are striving for ever-greater rewards while simultaneously minimizing threats and dangers. Such balanced behavior of approach-and-avoidance learning is surely helpful for surviving competition in a constantly changing environment," explained Stephan Lammel from the University of California, Berkeley.

Decisions, Dopamine and Expectations

Scientists from the University of Tsukuba, Japan, associate dopamine with choosing wisely and a person's ability to evaluate options to choose the most beneficial outcome. This can be as complex as a decision between life and death, or as simple as choosing what to eat for breakfast.

The brain's decision-making process is found to be a collection of neural activity within the prefrontal (front) and striatal (middle) regions, specifically in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). The OFC contains neurons that encode variables for internal processing as decisions are being made, comparing different options, and identifying which one to make.

At the same time, dopamine in the striatal region, or the midbrain, is encoding a "reward prediction error" signal which measures expectation versus reality. This dopamine signal drives the brain to choose the option that would result in an outcome that is better than expected.

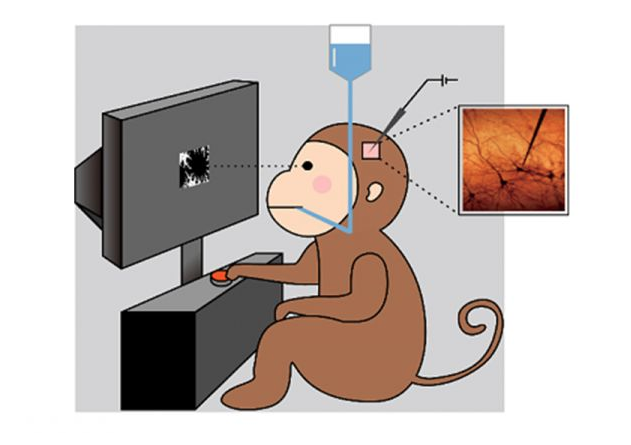

Professor Matsumoto explained that dopamine neurons "become very active after an animal receives an unexpected reward and become less active as expectations are learned." His team applied this principle in a game for monkeys.

Making Economic Decisions

The monkeys were taught how six pictures represented different reward levels. They could either choose an image and receive the associated reward or pass and get the reward from the next image.

Sometimes the monkeys would risk passing up an image with a mid-level reward for an anticipated larger reward of the next image. The dopamine levels on both parts of the brain were found active during decision making.

"These neurons especially reflect the entire integrated decision-making process," said Professor Matsumoto, "and we suspect that they send this decision out to other parts of the brain such as the orbitofrontal cortex, and finally to the muscles for an action to take place."

Some dopamine levels focused on the reward while other dopamine neurons dictated the final decision--like the difference between the instant gratification of an unhealthy food craving, yet levels go down when one decides to eat a healthy apple instead.

The brain activity associated with economic decisions, or neuroeconomics, is a relatively new field of study. With dopamine responsible for decisions, risks, and diseases, Professor Matsumoto adds, "Our research may thus provide insight into decision-making deficits that might be present in" illnesses such as Parkinson's.