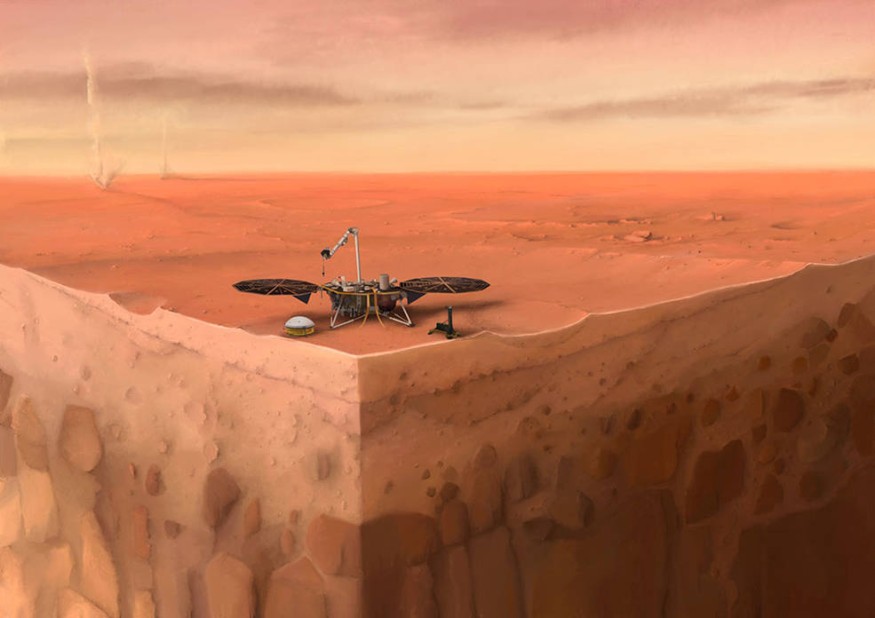

Scientists now have absolute figures to depict Mars' interior structure — including the Red Planet's crust and core.

The information comes from NASA's InSight probe, which has been monitoring Mars quakes since early 2019.

The NASA-led mission discovered that the typical thickness of Mars' crust is between 24 and 72 kilometers (15 to 50 miles), which is smaller than previously thought.

The size of the planet's core, though, is the most important discovery. It has a radius of 1,830 kilometers, which is more than prior estimations.

This is the first time that science has been able to trace the internal layers of a planet other than the Earth directly. It has been done before for the Moon, but Mars (with a total radius of 3,390 kilometers) is far greater.

Researchers can better comprehend the origin and evolution of different planetary bodies with this information.

"Unlike Earth, Mars has no tectonic plates; its crust is instead like one giant plate," NASA researchers wrote in a statement. "But faults, or rock fractures, still form in the Martian crust due to stresses caused by the slight shrinking of the planet as it continues to cool."

🔴 New findings using data from our @NASAInsight lander's seismometer reveal, for the first time, details about the deep interior of Mars.

— NASA (@NASA) July 22, 2021

What scientists learned about the depth and composition of the Red Planet's crust, mantle, and molten core: https://t.co/jF1tk7vtUq pic.twitter.com/bq5K9H74dT

Internal Layers Of Mars

InSight obtained its findings in the same way that seismologists investigate interior layers on Earth: by following seismic signals.

Waves of energy are released as a result of these events. Changes in their route and velocity will reveal the composition of the rocky materials through which the waves flow.

Hundreds of tremors have been detected by the Nasa probe's seismometer system, with a select few having the right qualities to "picture" Mars' innards over the last two years.

The instrument team, led by France and the United Kingdom, estimates that Mars' stiff outer section, or crust, is 20 km or 39 km (12.7 miles or 24.4) thick right beneath the probe (depending on the precise sub-layering that exists).

Extrapolating to the rest of the planet's known surface geology, Reuters said this predicts an average thickness of 24 to 72 kilometers (15 to 50 miles). The average thickness of the Earth's crust is 15 to 20 kilometers (9.5 to 20.7 miles). It can only reach 70 kilometers in a continental location like the Himalayas.

The number for the core, on the other hand, is really intriguing. Signals from "Marsquakes" bouncing off this metal feature indicate that it begins about halfway down from the surface, at a depth of roughly 1,560 kilometers, and that it is liquid. The majority of previous predictions called for a smaller core.

According to the mission crew, the new direct observations have two exciting effects.

The first is that Mars' known mass and moment of inertia suggest the core is far less thick than previously thought and that the iron-nickel alloy that dominates its composition must be heavily enriched in lighter elements like sulfur.

The mantle, which lies between the core and the crust, is the second consequence. This is now noticeably thinner than previously thought.

Again, based on Mars' known size, this mantle is unlikely to reach the pressures required for the mineral bridgmanite to become stable.

This rigid mineral envelopes the Earth's core, reducing convection and heat loss. Its lack on early Mars would have resulted in fast cooling.

This would have allowed for substantial convection in the metal core and a dynamo effect that would have driven a worldwide magnetic field at first. However, this has now been turned off. There is currently no evidence of a global magnetic field on the planet.

A series of scientific studies, titled "Seismic Detection of the Martian Core," published in Science magazine revealing Mars' interior structure. Along with them, Dr. Sanne Cottaar published a perspective titled "The Interior of Mars Revealed."

Check out more news and information on Space in Science Times.