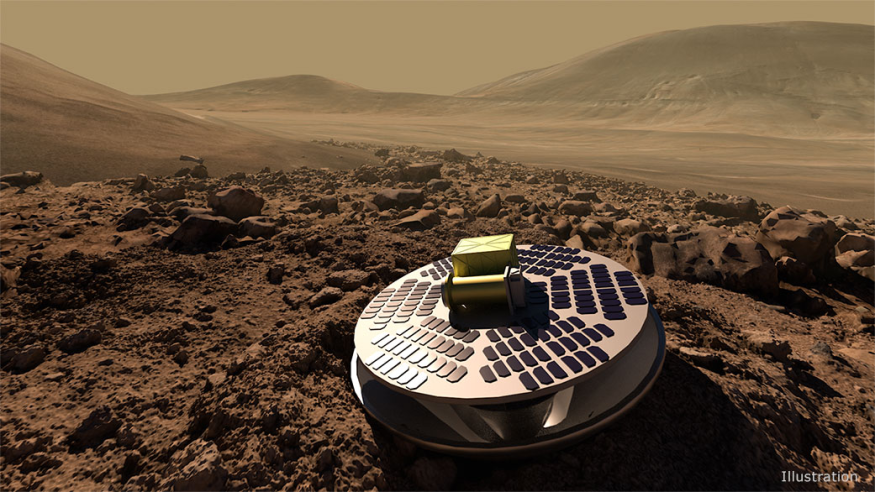

The revolutionary SHIELD lander is constructed to withstand a severe collision, much like a car's crumple zone. For nine times, NASA has landed safely a spacecraft on Mars, using sophisticated parachutes and enormous airbags, including jetpacks to secure the vehicle to the planet's surface. Scientists are currently testing to see if crashing is the quickest way to reach the Martian surface.

An experimental lander technology known as SHIELD (Simplified High Impact Energy Landing Device) will use an accordion-like, expandable base that functions like a car's crumple zone that distributes the energy of a heavy impact as opposed to slowing a spacecraft's elevated descent.

The JPL states that SHIELD will employ an accordion-like expandable base that behaves like a car's crumple zone as well as absorbs the impact of a heavy hit, as stated in the statement of NASA JPL. NASA used a full-scale model of SHIELD's attenuator, an inverted pyramid made of metal rings, and dropped electronics into it at a speed of more than 100 mph to test the novel method. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory described the experiment as a "smashing success."

Project manager for SHIELD Lou Giersch stated in the post, "The only hardware that's been broken were several plastic components we weren't bothered about."

Crumple Zone on the Martian Surface

The use of this technology, according to JPL, could significantly reduce the cost of Mars landings by "simplifying the terrifying entrance, descent, and landing procedure" and could lead to more touchdown possibilities on the lifeless planet. Giersch believed that they could venture into riskier regions where they wouldn't want to take the chance of attempting to land a $1 billion rover using our current landing capabilities.

This technology may have effects that go much beyond our immediate planetary neighbor. SHIELD associate Velibor Ćormarković added that they know SHIELD could do significant activities on planets or moons with denser atmospheres, as stated by The Byte in a report.

Ormarkovi recently tested vehicles that had crash dummies for the automotive sector. Several of these tests involve crashing the cars together into a barrier or other deformable obstacle while they are being pulled along on sleds at high speeds. Such sleds can be propelled in a variety of methods, one of which is by employing a sling similar to the stern release mechanism.

Successful Initial Smashing

Following an earlier report from NASA, the SHIELD crew assembled at the drop tower on Aug. 12 with a full-size prototype of the impact-absorbing collapsible attenuator, which is made up of an inverted pyramid of metal rings. To replicate the electronics a spacecraft might carry, they attached the attenuator to a grapple and placed a smartphone, a radio, and an accelerometer inside.

They were perspiring from the heat of summer as they witnessed SHIELD slowly ascend to the tower's top. The bows launcher rammed SHIELD through into the ground at about 110 miles per hour in under two seconds (177 kilometers per hour).

When a Mars lander approaches the surface, it is traveling at that velocity after being slowed down by atmospheric drag from its own initial velocity of 14,500 miles per hour (23,335 kilometers per hour) as it enters the Martian surface.

For this test, the scientists placed a piece of steel 2 inches (5 cm) thick on the soil to simulate a rougher impact than a spaceship would face on Mars. Previous SHIELD testing used a dirt "landing zone." Later, the onboard accelerometer revealed that SHIELD had been struck with such a force of approximately 1 million newtons, or the equivalent of 112 tons slamming into it.

In the test, SHIELD hit at a small angle, bounced up into the air for roughly 3.5 feet (1 meter), and then overturned. This is evident in high-speed video footage.

Overall the initial smash was a success for NASA JPL as per Giersch. The next phase is designing the lander's remaining part in 2023.

Check out more news and information on Space in Science Times.