The world has come a long way in the fight against polio, which began in the 1950s. Over the last few decades, efforts to eradicate this viral disease have prevented over 20 million cases of paralysis.

The End Game

In Afghanistan and Pakistan, pockets of wild polio persist but are shrinking. In Africa, a polio vaccine that includes live viruses has seeded outbreaks in the region. These are considered signs that health campaigns bring vaccine-derived episodes under control.

The final steps towards eradicating polio are formidable, and it is unclear when nations will finally reach this goal. Health authorities are planning what to do with the progress in eliminating the virus.

Even if poliovirus has not yet been eliminated, many people hope it can disappear within three years. Campaigns to eradicate polio have increased in intensity and funding in the past years to meet a deadline that has been postponed many times since efforts started in 1988.

The end of this disease is only the beginning of another effort to develop resilience to keep it away. Public health specialist Liam Donaldson from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine noted that people have signed up for polio eradication programs. Still, they have not signed up for the longer journey.

READ ALSO : US Reports First Polio Case Detected in New York; Unvaccinated Encouraged to Get Vaccine to Prevent Outbreak

Keeping the Virus From Coming Back

The challenge lies in the fact that eradication is not extinction. Poliovirus could still lurk in testing laboratories, manufacturing facilities, and even some people. According to virologist Konstantin Chumakov, mistakes years after the eradication can let polio into a vulnerable population where it could wreak havoc.

So far, smallpox is the only human disease declared wholly eradicated since 1980. Polio, on the other hand, is a more complex viral disease. Every smallpox infection produces symptoms, while polio can silently infect up to 1,000 people before causing paralysis. The other challenge is that polio might be caused not by the wild virus but by the vaccines developed to prevent it. To eradicate this disease means to get rid of both forms for good.

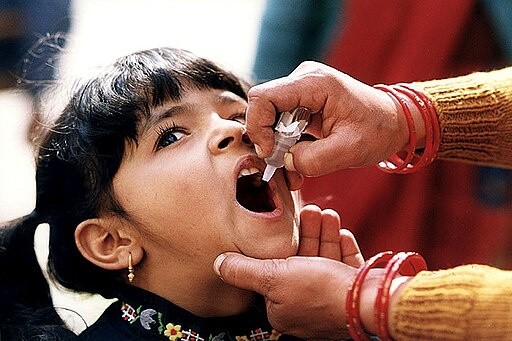

To achieve this goal, vaccination remains to be the most effective tool. Experts in industrialized, polio-free countries use inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), which does not prevent the virus from infecting the body but can protect a person from paralysis. According to CDC polio researcher Concepcion Estivariz, as long as the immunization levels with IPV remain high and sanitation is good, a rogue poliovirus will probably decline.

However, the inactivated vaccine cannot prevent transmission, so children in at-risk countries are given another type of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV). It contains an attenuated form of the live virus, which can stop the spread of the disease. Unfortunately, OPV has some downsides, with the vaccine itself causing paralysis. This can lead to outbreaks among people who have not been fully vaccinated.

As observed worldwide in recent months, polio-free communities are not polio-risk-free. Therefore, nations must step up and reaffirm their support to end polio for good.

Check out more news and information on Polio in Science Times.